Remembrance Day

by Ron tanner

March 1 in the Republic of the Marshall Islands is a national holiday. It used to be called Nuclear Victims’ Day, then Nuclear Survivors’ Day, and now Remembrance Day. The change reflects the nation’s determination to do more than voice lament and complaint for all they have suffered as the result of the U.S. government’s nuclear testing. But no one who knows the full story of nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands could blame the Marshallese for complaint or lament. Most Americans of a certain age have heard of the Bikini nuclear bomb test. But few Americans know, much less understand, the extent of nuclear testing that took place in this island nation between 1946 and 1958. During that time the U.S. Joint Task Force exploded a total of 67 nuclear bombs in the Marshall Islands. All of these were above-ground, under water, or ground-level tests. They created a stunning amount of fallout.

When the U.S. Navy introduced the Marshallese to the U.S. government’s intention to use the Marshall Islands as a nuclear testing grounds, the U.S. commander (filmed for PR purposes) asserted that the Marshallese were making sacrifices “for the benefit of mankind.” What did the Marshallese know of nuclear bombs? What did most people in the world know of this weapon? The Marshallese wanted to be good citizens. The Americans seemed to know what they were doing. Certainly they put on a good show--they had big boats; their leaders who wore impressive white uniforms with gleaming gold buttons; and apparently they had wealth beyond measure.

The first evacuees (from Bikini) were assured that they would soon return home. It seemed the tests would be only a temporary inconvenience. Even so, asking the Marshallese to move was asking a lot. To Americans, land is mostly a commodity to buy and sell. We are famous for moving our homes more frequently than any other people in the world. The Marshallese, by contrast, have been bound to their fragile atolls for three millennia, each clan, each family, associated with particular islands and particular parcels on those islands. The land is so sacred thatto plant and to bury are the same word: kallib. The graves of Marshallese ancestors nourish the crops of their descendants.

The first evacuees (from Bikini) were assured that they would soon return home. It seemed the tests would be only a temporary inconvenience. Even so, asking the Marshallese to move was asking a lot. To Americans, land is mostly a commodity to buy and sell. We are famous for moving our homes more frequently than any other people in the world. The Marshallese, by contrast, have been bound to their fragile atolls for three millennia, each clan, each family, associated with particular islands and particular parcels on those islands. The land is so sacred thatto plant and to bury are the same word: kallib. The graves of Marshallese ancestors nourish the crops of their descendants.

The physical effects of testing are still playing out. Some charge that the U.S. government used the Marshallese as guinea pigs because it made no effort to warn, much less evacuate, people who were in the path of the fallout. The most notorious incident occurred in 1954. Despite weather reports that warned of a shift in the wind, which would jeopardize several populated atolls, the U.S. Joint Task Force went ahead with its March 1 hydrogen bomb test -- a blast whose yield was 1,000 times greater than Hiroshima’s. In fact, this would be the U.S.’s most powerful test ever.

Unlike Hiroshima’s blast, which was well above the city, the Bravo blast was in-ground. It created a 20-mile-high upheaval of coral, water, animal, and plantlife, which then drifted in a huge cloud of raining fallout. It may have been anywhere from 1,000 to 10,000 times the fallout of Hiroshima.

The fallout drifted east over hundreds of square miles of populated islands. Inhabitants of the nearest islands, in the Rongelap atoll, experienced a snow of ash that, at first, was a wondrous sight. They’d heard of snow. But it quickly turned nightmarish, for the ash caused radiation burns. They would call this “the day of two suns.” No one had told them this was coming. They had no idea that everything they were drinking and eating was now contaminated. One inhabitant of nearby Likiep, who was eight at the time, recalls how a couple of days after the blast, he awoke to find the floor of his hut strewn with dead geckos that had fallen from the thatch roof where they had been exposed to the fallout. Canaries in a coal mine.

Two days after the blast, the Navy decided it should evacuate those who got caught down-wind because American servicemen at a weather station at nearby Rongerik sent a panicked report of fallout. The Navy moved some islanders, but not all. Apparently the commander in charge felt besieged by the growing number of refugees. He didn’t finish the job, leaving nearly 400 Marshallese on Aliuk. There was some attempt at follow-up. The U.S. sent doctors out to treat the victims. They assured the Marshallese that the worst was over. People would heal. The land would recover. Everything would return to normal. But then, a couple years later, it became frighteningly clear that things would not return to normal. Children exposed at an early age to the fallout were not growing. But the doctors were stymied. In 1963 they discovered, finally, that the victims’ thyroids were malfunctioning, depressing the pituitary gland, which regulates growth.

Two days after the blast, the Navy decided it should evacuate those who got caught down-wind because American servicemen at a weather station at nearby Rongerik sent a panicked report of fallout. The Navy moved some islanders, but not all. Apparently the commander in charge felt besieged by the growing number of refugees. He didn’t finish the job, leaving nearly 400 Marshallese on Aliuk. There was some attempt at follow-up. The U.S. sent doctors out to treat the victims. They assured the Marshallese that the worst was over. People would heal. The land would recover. Everything would return to normal. But then, a couple years later, it became frighteningly clear that things would not return to normal. Children exposed at an early age to the fallout were not growing. But the doctors were stymied. In 1963 they discovered, finally, that the victims’ thyroids were malfunctioning, depressing the pituitary gland, which regulates growth.

This was the beginning of decades of radiation-related ailments. And still the nuclear bombing persisted through 1958, despite the Marshallese pleas that it stop. Not until the 1970s did the Marshallese begin to seek compensation in the courts. Significantly, this was the decade the nation sued for independence, which came finally in 1986. As part of the Compact that guaranteed the nation’s sovereignty, the U.S. agreed to award the Marshallese $150 million in compensation for damages associated with nuclear testing. Interest from this fund was earmarked for disbursement to the victims and their families, but the funds were quickly eroded by the 1987 stock market crash and other factors. What is more, studies showed that the damage was far greater than the initial estimates, enumerated both in physical damage and in damages generated by the 1) loss of land use, 2) the cost of rehabilitating contaminated land, and 3) consequential damages resulting from such loss, repatriation, and rehabilitation.

This was the beginning of decades of radiation-related ailments. And still the nuclear bombing persisted through 1958, despite the Marshallese pleas that it stop. Not until the 1970s did the Marshallese begin to seek compensation in the courts. Significantly, this was the decade the nation sued for independence, which came finally in 1986. As part of the Compact that guaranteed the nation’s sovereignty, the U.S. agreed to award the Marshallese $150 million in compensation for damages associated with nuclear testing. Interest from this fund was earmarked for disbursement to the victims and their families, but the funds were quickly eroded by the 1987 stock market crash and other factors. What is more, studies showed that the damage was far greater than the initial estimates, enumerated both in physical damage and in damages generated by the 1) loss of land use, 2) the cost of rehabilitating contaminated land, and 3) consequential damages resulting from such loss, repatriation, and rehabilitation.

The Bikinians would accept a settlement of $360 million to reclaim Bikini atoll. But estimates for total reclamation reach as high as a billion. That’s a lot of money. But the Bikinians didn’t do the damage. And billion-plus is about what the U.S. government is spending every week in Iraq. Reportedly, 40% of the original Marshallese population that suffered the effects of radiation have died without receiving any compensation. They continue to sue through an organization called the Nuclear Claims Tribunal.

As many have observed, the U.S. testing of nuclear bombs was the product of profound arrogance, ignorance, and wishful thinking. The U.S. government hardly treated its own servicemen and women any better than the Marshallese. Untold numbers of servicemen and -women subjected themselves to exposure as their commanders told them there was nothing to fear. Just 10 hours after the first Bikini tests, Navy men were boarding the irradiated target ships in the Bikini lagoon and swimming in water that, only hours before, had been a seething cauldron of radiation. Years later these men would die of leukemia, thyroid cancer, and odd diseases that no doctor could fathom.

No single population on earth has had more exposure to and experience with the tragic effects of nuclear bombs than the Marshallese, a fact hinted at in the preamble to their constitution: “This society has survived, and has withstood the test of time, the impact of other cultures, the devastation of war, and the high price paid for the purposes of international peace and security.” (Emphasis added.) As a result, the Japanese have a great affinity for this nation. The Marshallese themselves have become international advocates of peace. Which brings us to Rembrance Day. On this day, they remember those who have suffered and those who continue to suffer, but they assert, too, that this is a proud nation that has much to celebrate and much to contribute to the world. One of those contributions is the story of this country’s remarkable survival.

No single population on earth has had more exposure to and experience with the tragic effects of nuclear bombs than the Marshallese, a fact hinted at in the preamble to their constitution: “This society has survived, and has withstood the test of time, the impact of other cultures, the devastation of war, and the high price paid for the purposes of international peace and security.” (Emphasis added.) As a result, the Japanese have a great affinity for this nation. The Marshallese themselves have become international advocates of peace. Which brings us to Rembrance Day. On this day, they remember those who have suffered and those who continue to suffer, but they assert, too, that this is a proud nation that has much to celebrate and much to contribute to the world. One of those contributions is the story of this country’s remarkable survival.

At a recent Remembrance Day memorial service, the U.S. Ambassador expressed “regret” and “concern” for all that has transpired as a result of the U.S. nuclear testing. He asserted that the friendship between the U.S. and the RMI remains unwavering and that the U.S. is giving a lot of money to help the Marshallese. A flier distributed by the quiet protestors outside the meeting hall disagreed with this assessment: “Justice for Survivors, equal to the Cost of the One (1) Week Iraq War,” the flier announced. In Marshallese: “Kajimwe na Suvivor ro, jona wot eo im Amedka ej jolok Nan Iraq ilo juon week.”

A number of other officials spoke at the ceremony, most of them in Marshallese. One Marshallese senator, who spoke in English, did not soft-peddle his views. At the time of the testing, he said, the Marshall Islands was “an occupied nation.” The move of testing from Nevada to the Marshall Islands made clear that “our land, our people, our nation were not seen as important as the people and property of the U.S. mainland.” Trusteeship in 1947, he observed, “was simply a legal mechanism to continue the testing that had already begun the year earlier.” As “trustees,” the Marshallese had no legal rights in the U.S. courts. Despite the eventual independence of the Marshall Islands, he concluded, “we are still seeking recognition of our rights in U.S. courts fifty-four years later.”

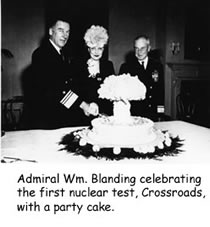

The assembled, elderly survivors stood and sang a song of their own composition. It was so sad, so haunting, it could be easily understood even by those who don't know Marshallese. If you do some research online, you may come across a collection of paintings housed by U.S. Naval Historical Center at the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C. The Navy collected paintings and illustrations from its servicemen who witnessed the first tests in 1946. It’s a bizarre assemblage of images, some striking, some lovely--all of them unsettling—and it underscores how naïve participants were at the beginning of an era that seemed so promising but went so thoroughly wrong.

The assembled, elderly survivors stood and sang a song of their own composition. It was so sad, so haunting, it could be easily understood even by those who don't know Marshallese. If you do some research online, you may come across a collection of paintings housed by U.S. Naval Historical Center at the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C. The Navy collected paintings and illustrations from its servicemen who witnessed the first tests in 1946. It’s a bizarre assemblage of images, some striking, some lovely--all of them unsettling—and it underscores how naïve participants were at the beginning of an era that seemed so promising but went so thoroughly wrong.